Which of the following sentences about promoting hate crime reporting is NOT true?

Tackling hate crime reporting barriers

By Carolina Navarro

Introduction

Different countries have implemented different strategies to combat the underreporting of hate crime. These strategies aim to address the reasons preventing hate crime victims and witnesses from reporting. Largely they consist of improving the current responses to hate crime reporting by law enforcement agencies as the main way to boost confidence in those institutions among victims and communities. However, best practices to promote hate crime reporting have gone beyond this and include the creation of alternative reporting systems and other broader strategies addressing the whole community.

Best practice guidelines to boost hate crime reporting have emerged from both experts’ recommendations and victims’ and communities’ voices. International agencies have systematised experts’ recommendations in guidebooks and manuals, which we will review across this module. The following studies have investigated solutions to hate crime reporting barriers from the perspective of specific minority groups and stakeholders:

- Cuerden & Blakemore (2019). Barriers to reporting hate crime: A Welsh perspective.

- Chakraborti & Hardy (2015). LGB&T hate crime reporting: Identifying barriers and solutions.

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2016). Ensuring justice for hate crime victims: Professional perspectives.

- Swadling, Napoli-Rangel, & Imran (2015). Hate crimes: Barriers to reporting and best practices.

| In this module

In this module, you will get to know the main recommended actions to tackle the hate crime reporting barriers that we reviewed in the previous module. We will offer a wide range of examples of best practice to promote hate crime reporting in the community. We review international recommendations on the matter as well as possible solutions suggested by representatives of a range of communities in Victoria. |

Can hate crime reporting be boosted?

Some experts have criticised the aspiration to full reporting, which is behind most hate crime policies, believing this is unrealistic and a wasted effort. Indeed, previous research found that some specific measures had limited impact on hate crime reporting rates. For example, Mason and colleagues found that the introduction of the Prejudice Motivated Crime Strategy in Victoria had little impact on increasing hate crime reporting.

However, evidence shows that the countries that have implemented comprehensive long-term strategies to promote hate crime reporting have obtained promising results, although still imperfect. For example, a recent study that compared the reporting of racist hate crimes to police in the UK and the US showed that, although these crimes are substantially underreported in both countries, overall, victim reporting has been increasing over time in the UK and decreasing in the US. The authors attributed these differences, in part, to the victim-centred policies of hate crime reporting in the UK, which differs from those in the US in terms of police interactions with victims, hate crime identification and hate crime training.

Therefore, there is evidence that, although hate-related incidents remain underreported, coordinated measures addressing different dimensions of hate crime reporting may help to mitigate the barriers that inhibit victim reporting. Let’s review these measures.

How do we remove hate crime reporting barriers?

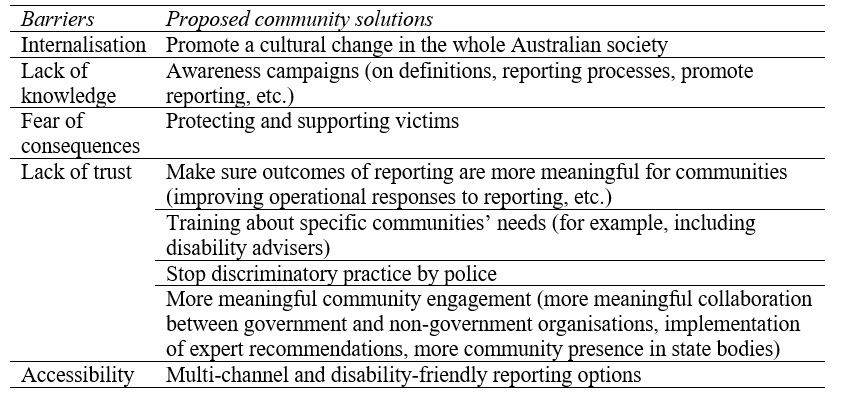

In the previous module about why victims of hate-related incidents are reluctant to report, we introduced five main categories of hate crime reporting barriers (i.e., internalisation, lack of awareness, fear of consequences, lack of trust, accessibility) corresponding to internal or external reporting barriers (see the extended table with barriers and definitions). In this section, we review the recommended actions to overcome internal and external reporting barriers. They are grouped into five types of solutions matching the five categories of reporting barriers. The next table summarises the best practice actions recommended for each reporting barrier.

A. Measures directed to individuals and communities: tackling internal reporting barriers

Many of the recommended actions to boost reporting behaviours among victims of hate crimes seek to facilitate cognitive changes in members of vulnerable groups and broader society. Through education, such measures provide information, promote change of beliefs and values, and challenge problematic worldviews.

Best practice no. 1: countering internalised beliefs

Educating the broad community and vulnerable groups about hate victimisation may help to create awareness that any expression of discrimination or hate toward members of the community based on their identity is unfair and unacceptable.

An example is the awareness campaign “Racism. It Stops with Me”, which was launched by the Australian Human Rights Commission. The campaign’s aim was to ensure that Australians recognise that racism is unacceptable in our community, and to empower individuals and organisations to prevent and respond effectively to racism.

Increasing community engagement by involving the public in the prevention of hate victimisation may help to mitigate the structural oppression that many vulnerable groups experience. However, as some representatives of minority groups from Victoria pointed out, a cultural change that involves the whole of Australian society is required to revert the structural oppression and historical trauma affecting their communities.

“This isn’t just a minorities’ issue, it is to society in general, so it needs everybody to call this out, it needs everybody to accept that our country is a multicultural country now, it’s not a European country and that none race is better than other. A lot of racial abuse is always because people say Aboriginal history and Australian history are different. We need that one narrative, all in the same but not separate.”

(Representative of an Aboriginal agency)

Best practice no.2: increasing community awareness

Clarity about what is and what is not a hate crime or hate incident is crucial to increase awareness within communities around hate crime and hate crime reporting. It is recommended to establish agreed working definitions of relevant terms (e.g., hate or bias crime, hate incidents, hate speech, prejudice, discrimination) between state agencies and relevant civil society organisations. An example is the definition of ‘prejudice-motivated incident’ established by the Practitioners Working Group on Tackling Hate in Victoria. We recommend checking out our training module Defining hate, violent extremism and terrorism: issues and perspectives for a discussion on why it is important to agree on common definitions, and a review on relevant hate-related concepts.

Working definition o prejudice motivated incident developed by the Practitioner Working Group on Tackling Hate in Victoria.

|

A prejudice-motivated incident is any incident in which any person believes that a person, property or group is targeted because of their race, religion, ethnicity, nationality, gender, sexual orientation, trans status, intersex status, disability, age or homelessness. |

Education initiatives are a key piece of any strategy to raise community awareness about what hate crime is and how to report it. This increased awareness, in turn, will increase the confidence of people in reporting hate crime.

Hate crime awareness campaigns are commonly used by police forces, communities, and local government to raise awareness, empower communities with the knowledge of their rights, and encourage victims and witnesses to report. To reach a diversity of social groups, awareness campaigns use a variety of media – mainstream media, social media, and the minority press – as well as poster campaigns in strategic community venues.

To be effective in encouraging people to report, experts recommend that awareness campaigns are based on positive messages and focused on specific groups. You can see an example of a positive message that was part of the Stop Hate Project, an awareness campaign launched in 2017 in the US by the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights under Law.

A great example of focused campaigns are those launched in the UK by TellMAMA. They produced poster campaigns to increase awareness on anti-Muslim hatred among Muslim women and men, to promote the reporting of anti-Muslim attacks, and to increase awareness on the importance of reporting hate crimes.

The Stop Hate Project offers two other excellent examples of focused awareness campaigns. One is a pamphlet for immigrants, which helps them to identify whether they have been victims of hate crimes and incidents and inform them on what to do. The second example is the campaign #Not Alone, which targets bystanders.

The next video highlights ways that allies can provide support to victims of hate attacks in the form of bystander intervention. This and other videos that conform the campaign are followed by resources on bystander intervention training.

Other highly recommended awareness strategies are creating education material for communities (e.g., manuals, brochures, and flowcharts) and engaging community leaders in awareness campaigns. An initiative that combines both strategies is the Community Response to Hate: Stop Hate Action Toolkit, launched by the Stop Hate Project and Not in Our Town. The action kit provides resources to assist community leaders, members and local government leaders with effective ways to respond to and prevent hate crimes and bias incidents.

Finally, a necessary component of an effective awareness campaign is promoting the reporting of hate crimes by victims and witnesses. Representatives of different communities in Victoria suggested disseminating within the community stories about good experiences of reporting and involving victims with successful reporting experiences who can support other victims on how to report. The need for a new approach where the focus is not on promoting reporting but in promoting outcomes for victims was also suggested.

“The focus should be ‘Yes, reporting can be long, but look at the potential outcomes that may happen, this could be you, you don’t have to sit in silent and normalise what happen or submit a report and think that’s the end gain.”

(Representative of a Muslim community organisation).

A recommended way to foster reporting of hate crime is informing the community about where and how victims and witnesses can report. Two examples of best practice in this regard are the Stop Hate Project website, which contains a step-by-step guide that orientates victims on what to do if they are targeted by hate, and a flowchart created by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights to illustrate civil society organisations about the decision-making process to collect and record data on hate crimes.

You can find more examples of educational awareness materials and resources here.

B. Measures directed to organisations responding to hate crime: tackling external reporting barriers

Our research suggests that boosting victims’ willingness to report would be of little use if the response they receive from authorities during and after reporting is not appropriate to the victims’ needs. This is why a core component of an effective strategy to combat the under-reporting of hate crime should be improving the response to hate crime reporting by involved agencies.

Best practice no.3: removing reasons to worry about the consequences of reporting

Best practice guidelines promoting hate crime reporting do not specifically focus on how to mitigate the victim’s fears on the consequences of reporting a hate-related incident. It is assumed that increased awareness of the victim’s rights, a consolidated social consensus around the unacceptability of hate victimisation, along with an improved response to hate crime reporting will, in turn, dismantle such fears. However, victims and communities have expectations in this regard.

Representatives of minority communities in Victoria pointed out the need for establishing minimal safety conditions that a reporting system should guarantee to victims to dissipate some of their apprehensions on the consequences of reporting. They also suggested concrete measures to safeguard the identity of LGBTIQ+ people who report. In line with this, experts say that allowing victims and witnesses to report hate crime anonymously, for example through a website or mobile phone app, could encourage greater reporting of homophobic and transphobic hate crime from both victims and witnesses. Also, providing victims with support services and an independent advocate who would support them through the process can offer victims a greater sense of safety and protection.

“Ensure them that they will be believed, guarantee that they don’t have to face the perpetrator and it [reporting] is not going to make the situation worse in any way. These are the three factors that are for any community really. For the LGBTIQ+ community, having confidence that the person I report to is a safe person, that’s fundamental; either they are part of the LGBTIQ community or an ally. Also, think of how it can be made in a relatively anonymous way, and not resulting in any trauma, so done in an efficient way.”

(Representative of an LGBTIQ+ agency)

In the next video, we asked Victoria Police how they can protect the identity of people reporting hate crimes.

Best practice no.4: addressing the lack of trust in statutory agencies

Hate crime research shows that the lack of trust in state agencies, mainly in the police, accounts for most of the reasons that victims don’t report. A recent study in Australia showed that more positive perceptions of police legitimacy and police cooperation are associated with a victim’s decision to report hate crime victimisation. Thus, any effective strategy to increase hate crime reporting necessarily needs to reverse community suspicion of state agencies and restore victims’ trust in police.

Increasing victims’ trust in state agencies requires restoring the confidence of communities with a long history of poor relationships with police and suspicion toward state agencies. As representatives of minority communities in Victoria repeatedly told us, this change needs to be initiated by state agencies. Experts recommend further meaningful engagement of the police and other frontline practitioners with communities (e.g., by attending social events in the community regularly and socialising in informal settings) and maintaining fluid communication between communities and police. This can help to develop a rapport and confidence among members of marginalised groups, which would, in turn, make them more likely to report their experiences of hate victimisation.

“It’s not up to the community; the work [restoring trust] needs to be done by the police.”

(Representative of an African agency)

“There is a lot of trust to be built. It’s not just ‘I recognise this is problematic’, it’s about translating that into action: ‘I recognise it, and this is what we are doing about it’.”

(Representative of a Muslim agency)

“The police has to demonstrate its commitment to stop disability discrimination.”

(Representative of an agency for people with disabilities)

When hate crime victims and members of minority communities are asked how they would like frontline practitioners to treat them when they report a hate crime, they express an expectation of being taken seriously and being treated with empathy and sensitivity. This is why improving victims’ treatment by frontline staff and the efficiency of police response to hate crime reporting are key recommended strategies to increase hate crime reporting.

The following are concrete recommended actions that police can take to communicate to the victim that the report is being taken seriously.

|

To counter victims’ perception that reporting hate crimes is pointless and to improve outcomes for victims it is necessary to improve operational police response. Many police forces across the globe have been making efforts in this direction. This video by The COPS Office and Not in Our Town highlights lessons learned by law enforcement in the US, demonstrating how to identify, investigate, and address hate crimes before they escalate to violence. You can watch the full documentary and review this guide that was designed as a tool to help law enforcement representatives facilitate discussions and training sessions for police officers.

To improve the operative police response to hate crime, different international organisations have systematised manuals of best practice guidelines for police forces to combat hate crime. Check out the following examples.

Best practice guidelines for police response to hate crime

|

Hate crimes are not only underreported but they are also underrecorded. This is why a particularly relevant area within best practice response to hate crime is the collection and recording of data by law enforcement authorities. This has been a major focus of the work developed by intergovernmental organisations in the EU, such as the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA), the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) and the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI), to address the chronic lack of reliable and comprehensive data on hate crimes across the OSCE region. These organisations, as well as the FBI in the US, have developed manuals and guidebooks on best practice data collection and recording. This is a selection of these guidebooks.

Best practice data collection and recording guidebooks

|

The treatment of victims by police staff is an area of police response to hate crime that requires improvements to diminish uninformed responses and discriminatory treatment of victims. The uninformed response by frontline staff needs further training strategies. Training police officers on how to receive hate crime reports, adequate ways to respond to the needs of specific groups (e.g., transgender, people with disabilities), and how to deal with people with traumatic experiences are all recommended actions to improve the quality of the victims’ treatment when they report hate crime to the police.

This video explains how the ODIHR helps counter hate crimes in OSCE countries by training national police to effectively identify, record and investigate such crimes. Find further details on their training program here. Please find here more examples of training resources for police and other organisations.

Stopping discriminatory treatment and victimisation of people based on their race or sexual orientation is, according to the representatives of minority communities in Victoria, a necessary condition to reverse distrust in police. Proposed solutions include training with a proactive approach to challenging discriminatory stereotypes and language; eliminating any treatment that is traumatic for victims.

“Ultimately, while police is engaged in informal racial profiling or targeting African communities, they are not going to be able to be a safe place for people to report hate crime. The police really need to sort their basic operational strategies out to remove racial profiling, get themselves clean up in that respect before they can offer themselves as safe to assist the community in hate crime.”

(Representative of an African community organisation)

Once both the police response to hate crime and the treatment of victims by frontline practitioners have been improved, a recommended strategy for challenging the scepticism around hate crime reporting is generating greater publicity of successful cases. These positive experiences of reporting may serve as examples that encourage other victims to report. The video “I survived my hate crime” by the FBI is a good example of this strategy.

In addition to measures to improve the current response to hate crime reporting by state agencies, best-practice recommendations include offering victims a wide range of third-party specialised reporting options that complement official reporting systems and compensate their deficiencies. When appropriately implemented and resourced, third-party organisations can provide a valuable reporting alternative for hate crime victims and a necessary means for hate crime monitoring.

This is an example of a third-party reporting system in the US.

Victorian representatives of minority communities suggested the creation of an integrated reporting system. Their expectation is not only for more reporting options for victims but for a reporting system that focuses on the victims’ needs and that is based on integrated and coordinated inter-agencies working together. The system should coordinate an articulated response to hate crime reporting by a network of organisations, including Victoria Police and governmental and non-profit organisations that work with different communities in Victoria. Such integrated reporting systems should:

– be victims’ needs centred

– ensure access to support services

– ensure participation of communities

– be based on coordination among organisations

– promote collaboration across communities

– offer a variety of specialised reporting options

– ensure adequate funding for participating CSOs

Countries that have implemented this victim-centred hate crime reporting approach, such as the UK, have achieved the best results internationally in terms of reporting rates, as a recent study shows.

Best practice no.5: improving accessibility

Finally, tackling access barriers is necessary to improve hate crime reporting. Best practices regarding access to reporting mechanisms call for reporting systems to provide victims with multichannel reporting options that are inclusive, respectful, and appropriate to all victims including those with any type of disability. Solutions in this regard include combining face-to-face and remote reporting systems (e.g., online forms, phone hotlines, websites or mobile phone apps), hate incident reporting centres run by police, adapting any reporting options to the linguistic needs and preferences of victims, and providing special aids for people with communication impairments (e.g., easy English versions of standard forms and written information for victims, establishing a centralised booking system for augmentative and alternative communication for use by Victoria Police and other agencies).

How can community organisations contribute to improve the recording of hate crimes and hate incident?

Various studies have demonstrated the value of the third-party model of response to hate crimes. For example, this study illustrated how a third-party hate crime/incident reporting system, one of the largest in the UK, has helped to support individuals and communities, including (but not limited to) those who do not want to report incidents to the police. Moreover, the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) has strongly recommended EU member states introduce third-party reporting as a means of overcoming hate crime underreporting. FRA also recommends that EU states enable third parties to institute proceedings against perpetrators of hate crime on behalf, or in support, of victims. In its guide for NGOs to prevent and respond to hate crimes, the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) highlights that, in addition to monitoring and reporting hate crimes, NGOs can also play a role in providing channels for people to bring complaints about discriminatory actions, including violence, by the police and other state agencies.

However, for CSOs to play an effective role as third-party reporting bodies, they must have adequate capacity and capability, as well as adjusting their reporting systems to best practice principles.

Making things easier for victims

International agencies have created guides and manuals for organisations, and experts have made recommendations on the best ways to assist victims of hate crime and recording their reports. Some leading non-government organisations have systematised their experience in collecting reports from hate crime victims and provided valuable recommendations.

These are some of the main of such sources of guidelines for non-police organisations:

- CEJI (2012). Guidelines for monitoring of hate crimes and hate motivated incidents

- Chahal (2016). Supporting victims of hate crime: a practitioner guide

- Chakraborti & Hardy (2016). Healing the harms: Identifying how best to support hate crime victims

- CST (2010). A guide to fighting hate crime

- ODIHR (2009). Preventing and responding to hate crimes: A resource guide for NGOs in the OSCE region

- Loudes & Paradis (2008). Handbook on monitoring and reporting homophobic and transphobic incidents

- Pullerits & colleagues (2020). Successes and challenges of delivering hate crime community projects

In particular, the CEJI guidebook provides examples of good practices by CSOs in the EU for both hate crime reporting and victims support. We also recommend you check the tips, lessons learned and best practices from Australian CSOs in our previous module on hate data collection in Australia.

From all this experts’ recommendation derive guiding principles that organisations can follow to ensure that they meet hate crime victims’ expectation of receiving an accessible and friendly reporting service that makes their experience of reporting easier. We encourage you to read the recommended sources for insights on other dimensions of the CSOs’ work in data collection (e.g., coordination with police and other organisations, operating procedures, data analysis and reporting). It is highly recommended that the views of the end-users of the service, that is victims and communities, are actively heard and considered during the design of the reporting system and working protocols around these principles are agreed.