Which of the following sentences about hate crime reporting is FALSE?

By Carolina Navarro

Introduction

Research into hate crime shows that: (1) those crimes are less reported to the police than non-hate crimes, and (2) most victims do not report their hate victimisation to the police or to other organisations. In the UK, one of the countries with better hate crime recording systems, only one in four victims of hate crime report to the police. This figure can be even lower for some vulnerable groups. For instance, the biggest study of hate crime victimisation, The Leicester Hate Crime Project, showed that only one out of 10 LGBTIQ+ people who suffer hate victimisation in the UK report to the police (see the report here). In Australia, the picture does not seem any better. The following studies used police records and data from a national survey to analyse hate crime reporting; they all found in the Australian context the same pattern of underreporting of hate crimes reported internationally.

Underreporting by victims has a negative impact on the ability of states to respond to hate crime. Understanding the reasons behind victims’ decisions not to report is a first step to tackle the obstacles and boost the reporting of hate victimisation.

| In this module

This module will help you to increase your understanding of hate crime victims’ reporting behaviours. We rely upon a review of international research and evidence from a recent study on hate crime reporting barriers in Victoria to respond to the following questions: what reasons inhibit victims of hate victimisation to report to the police or other third-party agencies? Are these reasons the same for victims from different communities? |

Why do most hate crime victims not report?

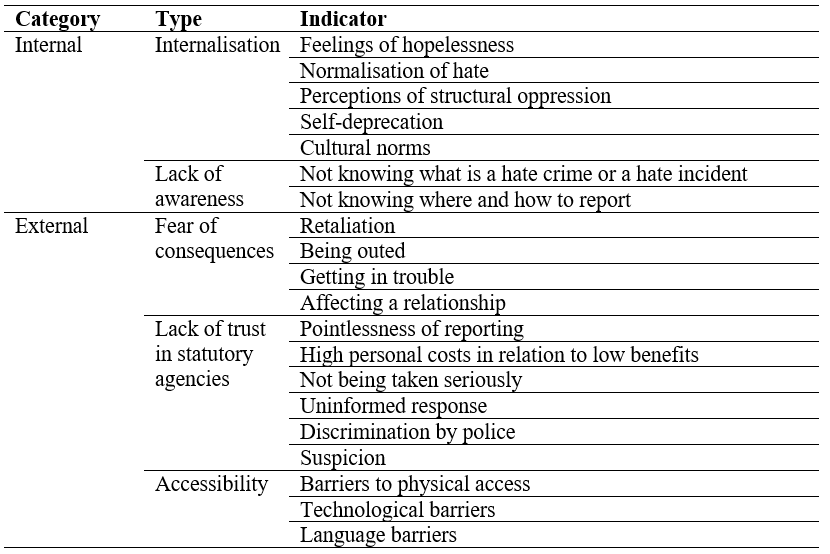

In this section, we introduce the reporting barriers along with vivid examples from our interviews with members of a variety of communities at risk of hate victimisation in Victoria. There are many studies looking at the reasons that victims of hate crime do not report victimisation to the police or third-party agencies (see a list of these studies here). The next table provides a synthesis of the barriers to reporting hate crime that appear in the academic literature. For further review of the barriers and their definitions, please check this extended table.

Understanding hate crime reporting barriers

The literature, there’s a great variety of reporting barriers. We propose a broad distinction between internal and external barriers, which originate either inside the victims’ psychology and communities, or outside.

A. INTERNAL REPORTING BARRIERS

Some of the reasons inhibiting hate crime reporting stem from the victims’ beliefs or knowledge about hate victimisation and its reporting. There are two types of internal barriers: internalisation and lack of awareness.

1. Internalisation

There are beliefs, ideologies, values or perceptions that normalise, validate or minimise hate victimisation. Such ideas contribute to the perception that discrimination, harassment, and abuse that some members of society experience cannot be modified and rather requires individuals to adapt and cope. Once internalised, these ideas can make victims and witnesses of hate-related incidents unwilling to report. Barriers in this category are ‘hopelessness’, ‘normalisation’, ‘structural oppression’, ‘self-deprecation’, and ‘cultural differences’.

For many victims, hopelessness is a barrier to reporting. Members of marginalised groups may accept repeated harassment and hostility as an unavoidable consequence of being different. These victims believe that change cannot occur and, instead, think that they must put up with the victimisation.

“There is also the issue of you born with this, you know, getting verbally abused and being racially vilified and all of these things. I’ve been racially abused my whole life; it just becomes a norm. I don’t know that it could be ever seen as something that could change or that there is a point in reporting it.”

(Representative of an organisation for Aboriginal communities)

The continuous experience of discrimination often results in the normalisation of hate victimisation. Members of marginalised groups often think that ‘everyday’ verbal abuse, online harassment, and other forms of targeted hostility are not serious enough to be reported to the police. Some even worry that they are wasting police time and resources or think that they have to deal with these issues by themselves. Conversely, victims are more inclined to report a hate incident if it involves deliberate damage to property or physical attack.

“The Jewish community is used to deal with these minor incidents. Nobody would ever report that.”

(Representative of a Jewish CSO)

Some of the more complex reasons for the underreporting of hate crime victims come from how minority groups, mainstream groups, and state agencies relate within society. Many communities suffer from structural discrimination, historical trauma and marginalisation from power structures, where covert racism, sexism, heterosexism, and other forms of structural oppression are an integral part of their everyday experiences. People from these marginalised groups may feel disempowered and unable to voice their concerns about hate incidents and have a general distrust of authority, which creates a barrier for reporting of hate crimes.

“The trans and gender-diverse community has been victim of systematic social abuse historically. We struggle because we have all this pain and wounds inside.”

(Transgender activist)

Many hate crime victims experience feelings of self-deprecation. Some may feel embarrassed about the incident and others may experience disempowerment associated with recognising oneself as a victim. Avoiding these feelings is a reason why some victims of hate crime prefer to do not report hate victimisation, as explained in this article.

“If you want to report a hate crime you have to previously take on the identity, ‘I’m a disabled person, I’m at risk’ and this is a huge issue form many people because they don’t think about themselves as disabled but as culturally and linguistically diverse people.”

(Representative of an organisation for deaf people)

Barriers to reporting hate incidents also stem from cultural differences between minority groups and mainstream society. For example, cultural values and beliefs within a community could determine or influence what can be reported and what should stay behind closed doors. Due to their vulnerable condition and cultural values around authority and obedience, some refugees may feel that they must be grateful to Australians and that they do not have the right to complain. In some cultures, the value of dealing with adversity by yourself may make people reluctant to report discrimination.

“Many immigrants and refugees are afraid of complaining about anything. They think ‘we came to their country so we should be thankful and respectful to them and not complain’. They are even stopping each other, ‘you shouldn’t report, you will put our community under question, you are a traitor’.”

(Representative of a human rights agency)

2. Lack of awareness

The second category of internal reporting barriers is the lack of understanding about hate crime and hate crime reporting by victims and witnesses. The reporting of hate-related events relies on people understanding what hate crime is, why it happens, and what people’s rights are when a hate incident affects them. Scarce awareness in the community of these points will affect the reporting of hate incidents.

A common reason why hate crime victims do not report is their lack of awareness about what hate crime is. Research has shown that many victims who have experienced an incident of hate may not recognise it as such, especially when there was no physical violence involved. Moreover, even knowing that something unfair has happened, victims of hate crime often do not report because of their scant understanding of discrimination laws and of their right to report incidents of hate. The scant awareness of hate crime also applies to non-victims and witnesses, which creates a barrier to the reporting of these incidents throughout the whole community.

“They don’t know what should be reported.”

(Representative of a Sikh community organisation)

For some communities, the terminology used to for the phenomenon (i.e., hate crime or prejudice-motivated crime) can be an obstacle to recognising a hate-related event. For example, the term crime, which is commonly associated with violent acts, may communicate the wrong message that reporting a hate-related event is relevant only if it is a violent crime. Additionally, some communities strongly identify with terms that describe specific forms of discrimination that affect them. For example, Aboriginal communities normally use the term racism rather than hate crime to describe discrimination affecting them. Members of other communities, too, may have difficulties with the term hate and may not feel their experiences reflected by such language.

We recommend this article by Wickes and colleagues about the impact of the new terminology of prejudice-motivated crime in Victoria.

“A lot of deaf and hard of hearing people in the community just don’t recognise that they are part of a minority, they don’t think they can be victims of a crime like this, they just don’t use that language.”

(Representative of a CSO for deaf people)

The lack of awareness about where to report also affects the chances that victims of hate incidents will report. This includes lack of information about the formal procedures to report and about alternative third-party reporting schemes. When alternative reporting options are in place, confusion about how such mechanisms work may also discourage victims from reporting.

“There are venues that they don’t know. They don’t know where to go and who to talk and how to access to their right to report a hate crime.”

(Representative of an organisation that works with African communities)

2. EXTERNAL REPORTING BARRIERS

Even when victims are able to recognise a hate-related event as unfair and know how to report it, many feel discouraged to report it due to their direct or indirect knowledge about what typically happens when a victim decides to report a hate crime. Some of the main reasons that prevent hate crime reporting come from these external factors.

3. Fear of consequences

It is common that victims of hate-related attacks feel apprehensions and insecurity about reporting their victimisation; they fear that negative consequences may result from a report and bring grave personal harm. Although such apprehensions are usual among hate crime victims from different groups, the feared consequences may vary across different communities. Barriers within this category are fear of ‘being outed’, ‘retaliation’, ‘getting in trouble’, and ‘affecting a relationship’.

For instance, research has shown that one of the main concerns among LBGTIQ+ people is that reporting homophobic and transphobic hate crimes could lead to them being ‘outed’. The fear of having their privacy compromised relates to apprehension on how data that ‘officially’ labels them as LBGTIQ+ will be stored and used. This fear affects both willingness to report to the police and using online reporting mechanisms by these communities.

For more information about LGBTIQ+ hate crime reporting, we suggest the following readings:

“They got your number and they now know you are a queer, that you are a victim of homophobic attacks and that you are homosexual, and that can make things worse for you.”

(Representative of an LGBTIQ+ organisation)

Some victims fear that reporting a hate crime may compromise their safety because it may lead to retaliation by the perpetrator. Other victims may also fear reprisals from the organisation where the victimisation happened that the perpetrator works for. This is the case, for instance, for people with disability who are care-dependant. These victims fear the withdrawal of benefits, rights, care, or supportive assistance if they make a complaint.

For more information about disability hate crime reporting, we suggest the following readings:

“There is a concern that if you report you may not be safe, for example, because the offender lives close to the person.”

(Representative of a Sikh community organisation)

Some victims are afraid that reporting their experience of hate crime may result in them getting in trouble or may make matters worse. For example, some people may be concerned about losing their job if the incidents occurred at the workplace; new immigrants may fear jeopardizing their immigration status, being reported or deported if they complain. They may not report in order to avoid being involved in a bigger conflict.

For more information about reporting hate crime against immigrants and refugees, we suggest this article.

“Especially with racism in the workplace, they don’t want to be identified as troublemakers, complainers, reporters, or betrayers; even inside the community.”

(Representative of a human rights agency)

Lastly, some victims fear that reporting a hate incident could affect an existing relationship, typically with the perpetrator. This often occurs in the context of dependency and unequal power relations. For example, fear of affecting the relationship with the perpetrator, frequently a family member or carer, is common among victims with high care needs, such as people with communication impairments. Also, some victims don’t want to report when the perpetrator is intimately related to the victim.

“When you have such an intimate relationship with the perpetrator, then is really hard for you to stand up for yourself and report that person.”

(Transgender activist)

4. Lack of trust in statutory agencies

The fourth category of reporting barriers is considered the major obstacle for hate crime reporting. Distrust and low expectations of the response by justice agencies, particularly distrust in the police, prevent most hate crime victims from reporting to those agencies. This is expressed through their disbelief in the usefulness of reporting (‘pointless to report’, ‘high personal costs’), apprehensions about their treatment by frontline staff (‘not being taken seriously’, ‘uninformed response’, ‘suspicion’), and negative expectations about the police response (‘discrimination by the police’).

Many hate crime victims do not report because they think that reporting is pointless and a waste of time. This perception is based on the meagre outcomes and direct benefits for victims once they report. Victims rarely see justice soon after reporting or positive actions being taken after reporting (e.g., arresting of the perpetrator) and frequently they are not kept updated about the progress of their case, which leaves many victims feeling reluctant to report again. Moreover, the lack of support systems discourages reporting by victims who seek contention and protection.

“It’s a waste of time. I have never heard about an experience of good results coming from someone who reported a hate incident.”

(Representative of an African CSO)

Often, victims undertake a cost–benefit analysis when considering whether to report a hate incident. Victims often feel that the reporting process is time-consuming, emotionally draining, and unlikely to yield a positive outcome. Thus, the investment needed from the victim to report and the high personal costs far outweigh the benefits of doing so. The result is a sense of apathy and the feeling that there is little point in reporting hate crime.

“They think reporting what happened will cost them time and money, you have to invest hours; and for what?”

(Representative of an African community organisation)

Very often, victims of hate crime anticipate that their reports will not be taken seriously and rather, they will receive unjust or negligent treatment by frontline staff. These victims think that either they will not be believed, or police officers and other practitioners are unwilling to address hate victimisation. This barrier is at the core of victims’ distrust in the police response to hate crime reporting.

“They think their complaints won’t be taken seriously; they feel ignored by the police.”

(Representative of an Arab community organisation)

Victims’ distrust of police also comes from the perception that frontline staff often lack the necessary training and understanding of the reality and needs of marginalised groups. As a consequence, many victims feel that most police officers are not skilled to appropriately support them, and so do not feel comfortable about reporting experiences of hate crime to police. However, the uninformed response by police officers is also perceived by victims as a result of insufficient training on hate crime, which discourages reporting of these crimes.

“The victims may have reported but the hate crimes were not captured by police; 40% of cases were not identified as same-sex attack or gender-diverse-prejudice motivated crime by the police.”

(Representative of an LGBTIQ+ community organisation)

Many members of marginalised groups are concerned about being treated with prejudice and stereotyped by police personnel when reporting hate crime. These victims fear being subject to discrimination and even victimisation by police staff. Police bias and negative police attitudes towards minority groups based on disability, race, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation and transgender status have been described. Such discriminatory behaviour creates a profound barrier that deters marginalised communities from reporting hate victimisation to the police.

“Young queer and trans people of colour absolutely mistrust the police. They feel they are receiving violence and disregard by the police.”

(Representative of an LGBTIQ+ organisation)

There is suspicion of state agencies among some marginalised communities. These groups often feel a large sense of distrust, in particular in the police and criminal justice system. For some communities, such suspicion stems from the historically poor relationship between state agencies and communities; for others, for example, immigrant groups, traumatic experiences with the police in their home countries increases distrust towards the police in their new country. However, for communities such as the Muslim, African, and LGBTIQ+ communities, the historical distrust in the police is deeply connected to policing strategies that affected them in the past or in the present.

“There has been a quite delicate relationship between the police and the community, and the way the Muslim community has been policed in the context of terrorism and violent extremism.”

(Representative of a Muslim community organisation).

5. Accessibility

Finally, there are also practical limitations that prevent hate crime victims from reporting. These are issues affecting the accessibility or adequacy of existing reporting mechanisms for victims. Two barriers fall within this category: ‘inaccessibility’ and ‘language limitations’.

Victims may decide to not report if the reporting mechanism is not easily accessible to them. Inaccessibility may occur due to inadequate location or poor wheelchair access of reporting centres, or when the victim is unfamiliar with ‘digital’ methods of reporting or has limited access to the internet or a phone. Moreover, online reporting methods can be perceived as too impersonal, inappropriate and discouraging for victims in need of immediate assistance (e.g., highly traumatised people).

“When someone has the power to report and the online system says ‘we’ll be in touch’ and two weeks go by, they don’t really reinforce to go down the process.”

(Representative of a Muslim community organisation).

The last reporting barrier relates to language limitations. Some victims from ethnic communities and immigrants who are not proficient in English or are not able to speak English at all may not feel confident that they will be understood if they report. Those with a disability may not be able to articulate what happened or have difficulty understanding the questions they are asked. Language limitations create a barrier when the reporting systems fail to adjust their procedures to some victims’ special linguistic or communication needs.

“The whole system is designed for people who can read, write and speak, but if you can’t, your chances of getting justice are very low. Most of our clients have communication impairments, which involve the inability to speak, read, or write. These victims are unable to communicate the abuse due to the lack of support and appropriate communication aids.”

(Representative of an organisation for people with communication impairments)

Gaps in hate crime reporting research in Australia

Research on why victims of hate crimes are reluctant to report in Australian is still limited. So far, these six studies have provided descriptions about hate crime reporting barriers in the Australian context:

In 2020, we conducted a new mixed-methods study on the specificity of the hate crime reporting barriers in the Victorian context for specific communities: religious groups, ethnic and sexual minorities, Indigenous, and people with disabilities. We summarize the key findings below.

Summary of key findings of perceived hate crime reporting barriers in Victoria:

|

|